These are the major topics found on this page.

- What vegetables can or should I plant?

- What vegetables do the food banks most want?

- What are the healthiest vegetables?

- When can each vegetable be planted?

- What is crop rotation, and why bother?

- Which vegetables should not be planted near each other?

- Why are some vegetables not recommended for our garden?

- Inspirational closing words I had to include somewhere on this part of the website and thought this was the best place.

The very first consideration ought to be “what would you most look forward to eating?” For some of us, the immediate answer would be either tomatoes or fresh greens.

-

- In both cases the produce ripening in our garden beds and going straight to the table is vastly superior to anything available in the supermarket. Early peas, green or wax beans fresh off the vine are also incomparable.

- Some of us like vegetables not often found in grocery stores: kohlrabi, spaghetti squash, rhubarb...

- Recipes often call for a teaspoon or so of a fresh herb. How do you have one readily at hand? Grow your own and also share them with others.

- Click here for a link to a chart listing the most common vegetable crops grown in the Pacific Northwest. That chart contains hyperlinks to other pages which give detailed information about each crop.

And if growing for food banks is — as it ought to be — a consideration there are some guidelines which they’ve provided for us:

-

- Stay with some of the basics: tomatoes, edible greens, beans, peas, cucumbers, squash, garlic.

- Fresh herbs are always welcome, and aren’t generally available otherwise to food banks.

- The same is true for hot peppers; it’s always nice to add spice.

• [Important note: All peppers donated to the food bank should be labeled as to their degree of heat — mild, medium, hot, really hot...]

Looking at the question a slightly different way, the first consideration might be “What vegetables are best for health?” The 14 healthiest are, in order:

- Spinach

- Carrots

- Broccoli

- Garlic

- Brussels sprouts

- Kale

- Green peas

- Swiss chard

- Ginger

- Asparagus

- Red cabbage

- Sweet potatoes

- Collard greens

- Kohlrabi

Another important consideration is what can be grown in the Pacific Northwest. The fact is, our climate makes this one of the most challenging places in the country for gardening. Soil temperatures and overnight air temperatures make it difficult to grow some of the more popular crops to maturity before the season ends.

Minimum Soil Temperatures for Seed Sowing and Germination:

- 35°F: lettuce, onion, parsnip, spinach.

- 40°F: beet, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrot, cauliflower,collards, Asian greens, Chinese cabbage, fava beans, kale, kohlrabi,mustard, arugula, radish, Swiss chard, turnip, pea, radish, rutabaga.

- 50°F: asparagus, celery, celeriac, corn, tomato.

- 60°F: bean, cucumber, eggplant, muskmelon, pepper, pumpkin, squash, watermelon.

Soil Temperature Needed for 70% Germination:

- 45°F: beets, lettuce, parsley, spinach.

- 50°F: broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrot, cauliflower, collards, Asian greens, Chinese cabbage, fava beans, kale, kohlrabi, mustard, arugula, radish, Swiss chard, turnip, pea, radish, rutabaga.

- 55°F: cabbage, corn, Swiss chard, tomatoes.

- 65°F: cucumbers, peppers.

- 70°F: beans, cantaloupe, melons, squash.

- 75°F: eggplant, okra, pumpkins.

Optimal Soil Temperature for Germination (near 100% germination):

- 65°F: parsnip.

- 70°F: spinach.

- 75°F: asparagus, lettuce, onion, parsley.

- 80°F: bean, carrot.

- 85°F: beet, cabbage, eggplant, pepper, radish, Swiss chard, tomato, turnip.

- 90°F: muskmelon.

- 95°F: corn, cucumber, pumpkin, squash, watermelon

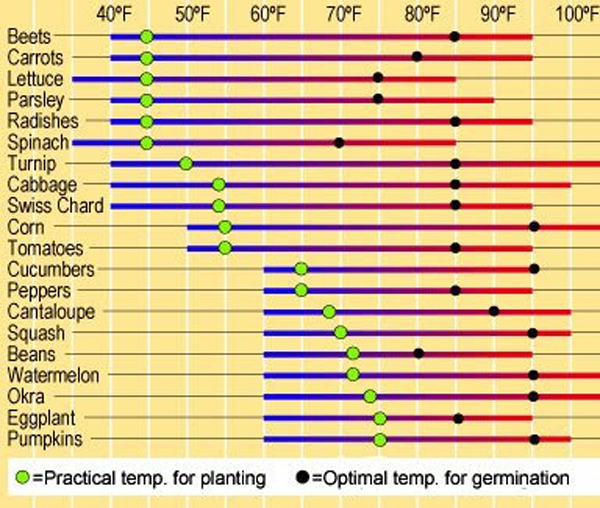

Here is a graphic condensing the two kinds of temperature limits:

“Bad Neighbors.”

A number of crops have “allelopathic behaviors” — they can produce chemicals that impede the vital systems of competing plants. Such common crops as beans, beets, broccoli, cabbage, cucumbers, peas, sunflowers and tomatoes can affect specific other crops.

Click here for Some specific, common examples.

Crops that don’t appear on the page of “Vegetable Crops With Links,” and reasons why they don’t:

-

- Asparagus — is a perennial. It takes 2 to 3 years to produce its first crop.

- Cauliflower — described as “finicky,” it is highly sensitive to temperature changes, soil conditions and watering practices. In addition, it may take from 85 to 120 days to grow a fully developed head.

- Celery — described as “one of the more difficult crops to grow at home,” it can also take up to 140 days to come to harvest.

- Corn — a planting of sweet corn requires a certain number of plants to ensure sufficient pollination to develop edible cobs. Few gardeners care to devote a large enough portion of their beds to provide that.

- Fennel — while a very useful and delicious vegetable, fennel is not a good neighbor in a vegetable garden. It will actually inhibit the growth of several vegetables, including tomatoes.

- Melons — while there are varieties of melons that can mature during our short growing season, those must be selected specifically. Even so, expert gardeners who do grow them list a number of special steps they have to take in order to produce a crop.

- Mint — It’s actually a stipulation in the Gardener’s Agreement that no one will grow mint. It becomes invasive and we’ve had a very unhappy history with mint getting loose in beds.

- Potatoes — The food banks have specifically said they have more than sufficient supply of ordinary potatoes from commercial growers. They do have a certain demand for fingerlings and other varieties of smaller potatoes. As for the larger ones, you may grow them for your own use if you care to, but for the price of spuds in the grocery stores it’s not the best use of a garden bed.

- Rhubarb — we’ve had gardeners grow rhubarb in the past, and it’s always seemed to be welcome addition to our contributions to food banks; however, it’s another perennial — taking 2 to 3 years to begin producing decent harvests. Also, it takes up a significant amount of space in a garden bed and develops a very large-sized root system. None of this is to say it shouldn’t be grown in the garden, only that rhubarb presents a number of challenges. Anyone interested in growing it should do their own research.

- Strawberries — Again, it’s an item in the Gardener’s Agreement that we don’t grow strawberries. And again, it’s a matter of an unhappy history: non- productive strawberry plants spreading out to take over an entire bed after being left untended.

Which leads into the final statement in “What To Grow” —

——————————————

Just about everyone signs up to join the DuPont Community Garden in the anticipation of enjoying bountiful harvests of very tasty, nutritious and healthful vegetables throughout the growing season.

Sometimes their fantasies come true; but sometimes they don’t. Success in gardening depends on various things coming together: seed or start selection, soil and air temperatures, soil structure and levels of nutrients and moisture, presence or absence of pests and diseases, the gardener’s ability to train the plant in the way it will grow best....

Everyone who’s been part of the garden for very long has had experiences with great successes but also with dismal failures. Each on those experiences has given us insights into what works and what doesn’t; what to watch out for and how to cope with threats to our crops. Sharing those insights with everyone else in the garden is one of the most important ways we truly become a community garden.

If you have an insight, an experience, a lesson-learned, or a valuable hint you think might benefit other members of the garden, please feel free to share it: mikef@dupontcommunitygarden.org