DuPont Community Garden Fruit Trees/Shrubs

To ensure the continuity of care for the fruit trees and shrubs in the Garden, I am presenting the information and lessons learned that I accumulated while caring for them. Each type of fruit will have a separate section and the information presented by topic rather than tied to a calendar since we’ve experienced such a wide variation in weather from year to year.

Pears

Currently, there are five varieties of pears. Two Orcas and Two Rescue pears are being grown as espalier trees on heavy wire mesh at the southern end of the Garden. One specimen of each — Bartlett, Sekel and Honeysweet — are being espaliered in above-ground containers along the North fence.

The Honeysweet was purchased at the same time as the Orcas and Rescue trees, but is much smaller since it has struggled with disease and insects every year. The variety was listed as “moderately resistant to Fireblight,” but suffered from that disease in its first two years.

The Bartlett has also struggled with Fireblight, so it was relocated to the end of the Garden opposite the Orcas and Rescues.

The Sekel only came into bearing — producing four pears — in 2021. They are a very small pear, but intensely sweet. In 2022 it had an early and very severe infestation of pear blister mite (which I tried to control by removing all infested leaves and then spraying with Neem oil). It produced no harvestable pears in 2023.

As of Sept 2023, there remains the question as to whether it’s worth trying to nurse the Honeysweet, Bartlett and Sekel trees along or if we should get rid of them and plant something more productive along the North fence line.

Pruning:

After they’ve lost their leaves in the Fall and prior to buds swelling for the following season, the espaliered trees need to be pruned to continue in that form. I have generally waited until around Christmas when I’m sure they’re in full dormancy. Please refer to either/both books on pruning for espalier or on-line videos.

On the other hand, by waiting until after the growing season is over the trees have been allowed to develop long and very vigorous suckers — or “water sprouts.” During the 2023 growing season, I kept most of those suckers cut back. It didn’t seem to have a negative effect on the trees, but did seem to get the trees to put more growth into the fruit. I recommend that be continued in the future.

In any case, to reduce the spread of diseases, pruning shears must be kept sharp and should be dipped in alcohol, bleach or some other sterilizing liquid prior to moving from one area of a tree to another; certainly before moving to another tree.

Spraying for pest control:

Pears should be sprayed with a dormant oil to kill over-wintering insect eggs. I found that I needed to be very aggressive in this program to contend with the pear blister mite that cost us good yields for two years in a row. The first application should before the leaf buds begin to swell, and applications should be repeated at 3 to 4 week intervals up until bud break. Three applications seem to work well.

Don’t spray with dormant oils when the temperature is below 40 degrees as the emulsifiers won’t be effective at that low range. Also avoid spraying if rain is expected in the next 24 hours.

Hand pollinating:

Since the pear trees bloom when the weather is too cool for pollinating insects to be active, I’ve only had significant crop yields by hand pollinating. And as most pears aren’t self-fertile, it’s important to cross-pollinate them. (Honeysweet are said to be self-fertile. I’d try it both ways to be on the safe side.) Refer to the paragraph at the end of this page on Hand Pollinating for details and procedures.

Irrigation:

Fruit trees do best with one or two deep waterings each week. Two gallon-per-hour emitters work best on our system.

Pest control during growing season:

If pear blister mites still show up during the growing season you can attempt to control them with Neem oil, but I didn’t see that it had much effect. The best solution — if the mites do begin to appear — is apparently to cut off the affected branches and dispose of them at home.

Fireblight is a very destructive disease of pears, and very difficult to control. Again, cutting off — and sterilizing the shears between each cut — and disposing of infected branches into the trash is the best control. It’s also recommended to spray for insects that help spread the disease. Neem oil or insecticidal soaps can be used.

Please read up on this disease on one of the many web pages devoted to its control.

Leaf miner is an insect pest that is protected from spraying since the eggs were injected between the surfaces of the leaves and the larvae are growing in a protected environment. At best you can just monitor the trees to detect any leaves in the process being skeletonized, pick them off and grind them into the dirt to kill the larvae. Since leaf miner produce three generations per season, the sooner they can be controlled the better.

In 2023 we also had some tent worm show up on a couple of trees. They’re easy enough to eliminate by hand, but if left untreated they can seriously defoliate a tree in a matter of days. Early detection is vital.

So far (knocking on wood) we haven’t had any problems with coddling moth (the “worms” in pears). If they should start to show up you can shop at some of the better nurseries (Portland Avenue in Tacoma, The Barn south of Tumwater) for traps.

Also: In late 2021 I took it upon myself to begin going through the City’s tree nursery, north of the garden, and remove all of the apples — either on the ground or still on the trees — to prevent them from overwintering any pests. It’s well worth while to continue that while fruit trees continue to grow there.

Harvest:

Since pears ripen from the inside out, if you wait for them to look ripe before picking them they’ll be too mealy to be edible. Pears should be picked when the first ones start to drop off the trees and the rest come off easily when you lift the fruit to test the stem. They can continue to ripen for 2 to 4 weeks before they’re ready to send to the food bank.

Sanitation:

The most effective way to control insect, fungus and bacterial pests is to remove all leaves from the area after they’ve fallen off. Otherwise the spores of bacteria and fungus will overwinter and re-infect the trees in the next season. Insect eggs will overwinter as well.

I find it’s most effective to begin with a lawn vacuum, followed by using the leaf blower to collect the remnants against a fence line. The final step should be the grubbing around on the ground to collect the last few.

Fertilizing:

The recommendation is to apply a 10-10-10 fertilizer, probably in Early Spring before growth starts. In 2023 I used Jobe fertilizer spikes — 2 per tree — that were specifically formulated for fruit trees.

Figs

The initial purchase of figs trees was four Brown Turkey Figs from Raintree Nursery in Morton, WA. The catalog described the Brown Turkey as being “one of the most reliable in our region.” It categorized the variety as suitable for hardiness zones 7 through 11 (DuPont is described as being in zone 8b), and that “the hardy tree will bear heavily and can have two crops of large delicious fruit a year.”

Obviously, I’ve been doing something wrong.

Winter hardiness has been the biggest issue. Two of the four trees have frozen back to the crown in both winters that they’ve been planted outside —despite being protected last winter. Since those two have resprouted from the rootstock, it’s not known what variety of fig they are but they do resemble Brown Turkish.

Also, [as of 2022] none of them have yet borne fruit early enough in the season to provide a harvest. Leticia assures me that when the trees are sufficiently established they will adopt their described fruiting pattern.

2023 Update: The two figs that have frozen back each Winter came back again this year, growing even larger than before and bearing a significant amount of fruit — although very little of it matured prior to the first hard frost.

Irrigation:

As with the pears, recommendations are for one — two at the most — deep waterings each week.

Pest control:

To date, the figs have seemed to be free of pests; however, if/when they begin fruiting earlier in the season we will quite probably see them attracting yellow jackets. Yellow jacket traps should take care of that problem.

Pruning:

Unlike the pears, the figs were not trained as espaliers before we planted them. At first, I attempted to train them into three-tiered espaliers, but they didn’t take to that pattern. Literature recommends that figs be espaliered into a fan pattern.

The biggest problem has been winter die-back of branches chosen as leaders. Also is the problem that side branches aren’t always conveniently located parallel to the fencing material, but will require more long-term bending and pruning.

Blueberries

Like the figs, we purchased the blueberry plants from Raintree Nursery. All 8 plants were of the Blueray variety. This may or may not have been prudent as I subsequently read that while blueberry plants are only partially self-fertile; they bear more heavily when cross pollinated. If we have occasion to replace any of our bushes we should definitely plant another variety.

While the blueberries have done quite well in most years, we lost most of the 2021 crop when the irrigation timer was interrupted (probably by curious little fingers) just prior to a record-breaking heat wave. Two plants which appeared to be dead did revive later on and produced new foliage, so it is hoped that there will be no long term damage.

Fertilizing: A salient feature of blueberries is their requirement for an acid soil; 4.5 to 5.5. We have tried to maintain this level by both the use of fertilizer specifically formulated for blueberries and by getting leftover coffee grounds from Starbucks. Still, we should be doing more regular testing of the soil during the early growing season.

Irrigation:

It is recommended that blueberry plants receive two deep waterings per week. I haven’t been following this pattern, although I intend to start for the 2022 season.

Pest control:

By far, the most severe pests for growing blueberries are birds. We have successfully kept the birds frustrated by enclosing the bushes in bird netting.

During the 2023 season, the netting was left up on one plant — either while someone was weeding in the bed or picking berries. The birds had the plant cleaned of fruit in about two days.

Pruning/shaping:

Eventually, the blueberry bushes should grow to somewhere between 4 and 6 feet tall and wide. As the plants continue to grow, we may want to extend the netting so that all 8 enclosures are merged into one.

2023 update. This was the first year when the blueberries produced a substantial amount of new growth. This will allow me to prune out much of the older wood during the dormant period, the result of which should be a substantial crop of berries next season.

Grapes

The two grape vines, planted in containers at the back of the pergola, were brought over from the previous site. I have no idea what variety they are, but are probably some variety of green table grape (as opposed to a wine producing variety).

Based on the description of grapes as growing from 10 to 20 feet per year, I’d have to say that ours have under-performed. The hope was that — grape yield notwithstanding — the two vines would cover the pergola and provide a Mediterranean environment. It hasn’t yet and I’m not sure why. The literature I’ve read suggests that growing grapes successfully is a bit on an art form.

Fertilizing:

I’ve been hesitant to add fertilizer to the grape containers since the literature has warnings against over-fertilizing the vines. Still, I intend to add some commercial compost to each box for the 2022 season.

Irrigation:

As with the other fruit crops, the recommendation is to provide one to two deep waterings per week.

Pest Control:

While there are a number of pests listed for grapes, I think the only two we need to be concerned with at this time are birds and powdery mildew — birds because they already consume a noticeable amount of each crop, and powdery mildew because it’s so prevalent in the rest of the garden already.

Whether or not we want to go to the expense of covering the vines with bird netting is a cost v. benefit trade-off we might want to address. If the main value of the grapes is the shade and aesthetic quality they provide, we can just as well forego bird netting there.

We need to continue to aggressively monitor and deal with any powdery mildew if/when it shows up.

Pruning:

For two seasons, I tried to prune side branches and encourage the development of three or four leaders for each vine. Since this apparently hadn’t worked I didn’t do any pruning prior to the 2022 growing season to see how the plants themselves want to develop. That didn’t seem to make much difference, so during the early months of 2023 I tried more aggressively cutting back on side branches and fastening leaders to the top boards of the pergola. This seems to have helped, and the vines now cover most of the eastern half of the pergola cover.

Hand Pollination of Fruit Trees

Purpose:

Pomaceous fruit trees, such as apples and pears, are only rarely self-fertile. In other words, the pollen from a Red Delicious apple blossom cannot pollinate another Red Delicious blossom — whether on the same tree or any other of the same variety. In order to produce a crop of apples, at least two varieties of apple need to be planted in proximity to each other. (Gravensteins are one exception to this rule; however, even with self-fertilizing varieties crop yields are much smaller than they would be with cross-pollination.)

Principles:

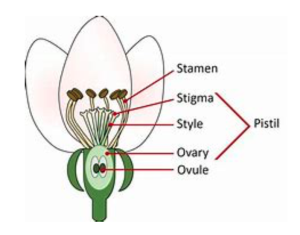

Pollination of fruit blossoms is such a clear example of sexual reproduction that it has been used as a “go-to” explanation of the process. In essence, it involves the transfer of genetically-coded material from one blossom to another. To achieve this, evolution has produced blossoms with distinctly male and female parts:

Pollen is produced on the pad-looking ends of the stamen — the “guy” parts. Pollination occurs when it’s deposited onto the sticky surface of the pistil which transfers it down to the ovary.

While a variety of insects, animals and even wind can transport pollen from the stamen of one blossom to the pistil of another, the primary pollinators of apple and pear trees are honeybees. Mason bees, bumblebees and other insects also play an important, although smaller, role in successful pollination. But without honeybees actively involved, crops tend to be smaller.

Honeybees are most active when the environment is suitable for them. Honey bees (Apis melifera, if you’re ever on Jeopardy) prefer weather of at least 65 degrees, free of rain or strong wind gusts. Unfortunately, those conditions haven’t generally coincided with the peak blossom times of our fruit trees here in DuPont. By the time those conditions exist, our Community Garden pear trees have finished blooming and can no longer be pollinated.

(In the Spring of 2023 as I began hand-pollinating the espaliered Orcas and Rescue pear trees in the Community Garden I noted a number of smaller insects crawling in and out of the blossoms and wondered if my efforts were even necessary. Therefore, I stopped hand-pollinating after completing three of the four trees. At harvest time, the three trees I’d hand-pollinated produced a record crop of 108 pounds of pears. The fourth tree had one, lone pear on it. Lesson learned.)

Another note: Just as different varieties tend to ripen at different times of the year, they also have their peak blossom days at different times. That’s why - especially with the heirloom apples — it’s important to monitor the trees for their peak blossom times and to mark those which have already been handpollinated (to avoid removing fertilized blossoms).

Process:

There are a number of techniques for hand-pollinating fruit trees. You can get a sample of them by searching “Hand Pollination” on the Internet. What I’ll describe here is my own technique.

First, collect all of the blossoms you think you’ll need for a supply of pollen. Paper or plastic drinking cups, properly labeled, will do fine. I use a pair of small scissors to snip selected blossoms off random parts of each tree.

“Selected” means that I pick blossoms that have a sufficient number of stamens on them. As you look closely, you’ll notice that the ratio of stamens to pistils varies from blossom to blossom. (Also, as noted below, since you don’t want as much fruit growing toward the end of young branches, those areas may be the best for collecting blossoms for pollen donors.)

Next, I use the scissors to trim the petals off each of the blossoms — exposing the stamens for better contact with the target pistils — and then carefully set the trimmed blossoms back into the container. If there is later an accumulation of pollen in the bottom of the container you can then use the Q-tip or brush to apply it.

In the Community Garden, the choice of which variety to cross with which has been simple since there were only two main varieties — Orcas and Rescue. (The other varieties at the other end of the garden were pollinated with leftover blossoms from the two main varieties.) In the Heirloom Orchard or tree nursery, I would recommend mixing things up a bit more — pollinating blossoms on Tree A with stamens from Trees B, C and D for example. This is because there are compatibility issues between some varieties, and we don’t yet know enough about our orchard trees to predict those.

As the above photos show, cross-pollinating is often done by shaking the pollen into a container and then applying it to the target pistil with an artist brush, a Q-tip, or other tool. However inefficient it may be, I’ve had acceptable results from just brushing the stamens up against the pistil, using one male blossom to pollinate three females.

When pollinating non-espaliered trees, you will want to consider on which parts of the tree you want fruit to be grown. Heavy concentrations of fruit further out on a limb can create enough leverage to cause the branch to split away from the trunk. On the other hand, you don’t want fruit growing too close to the center of the tree since it won’t develop the good colors as will fruit exposed to direct sunlight.

It’s very important to mark which branches or which trees have been pollinated. That way you won’t accidentally remove pollinated blossoms to use in pollinating other trees later on. Also, it lets you bypass some trees that aren’t yet fully in bloom during a given week and still pollinate them later.

Finally, it needs to be noted that apples and pears tend to be “biennial bearers” — that is, they will bear heavy crops during every other year; intervening years can be quite disappointing.